By Kristie Dickinson

In Michigan, I had been the owner of a freelance court reporting firm. I took depositions and produced my own work but also produced the work of the women who worked for me. I always worked 6 a.m. to 10 p.m., seven days a week. It sounds like a lot, but the good thing about doing freelance work is that you can take breaks and vacations whenever you want. My dog-walk breaks were about 10 a.m., 2 p.m., and 6 p.m. Neighbors sometimes asked if I worked because I was out walking in the middle of the day. Little did they know.

When I moved to California, I knew work in the new world of official court reporting was going to be different because, for the first time since I was 22, I was going to be working for someone else. I would be working inside the courts themselves versus taking out-of-court testimony. It would be early to work and late getting home. It would be no more dog walks whenever I wanted to stretch my legs. It would be not having any say in the work that I reported.

Never having worked for someone else, I’m still trying to figure things out now, a year and three months later; so you can imagine how overwhelmed I felt the first few days and months.

The first day and a half consisted of a kind of class where they handed out materials and instructed us. We learned what was expected of us, benefits we would receive, procedures, more benefits, dress codes, policies, and, well, more benefits. I checked out after the first round of benefits so, to this day, I’m not really sure what else is floating around out there. I decided to take it on an as-needed basis.

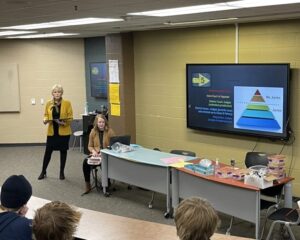

Then came the shadowing. I would sit in with other reporters, getting exposed to the proceedings in different kinds of courtrooms.

One of the differences between depositions and courtrooms is that I feel very in control in a deposition. There are usually three to six other people present in the room, and I feel like I run the show as far as telling people to slow down or to speak one at a time.

In a courtroom, the reporter is still expected to control things to make sure they make an accurate record; but, instead of three or four other people in the room, there can be anywhere from seven to twenty people looking at you like you can’t do your job when you tell someone to slow down. There’s performance pressure.

Another difference is courtrooms can be very large, and the acoustics can be quite inadequate. I suddenly wished I’d responded to that infomercial for the Miracle Ear. There were mumblers, interrupters, heavy accents, interpreters speaking nearby that made me feel like I was hearing voices in my head, and then there were the often not-so-quiet conversations coming from the audience. If the bailiff didn’t shush them, the reporter I was shadowing would tell people in the audience to be quiet. For someone who prefers to remain invisible in a courtroom, raising my voice to tell people 30 feet away to zip it is daunting.

Vocabulary was another obstacle in the new world. They pronounce things differently here. For instance, they pronounce “voir dire” phonetically, whereas Michiganders pronounce it with a French flare. I still chuckle when I hear people pronounce it here.

There were also new case names to learn, but the hardest things to learn were city names. Because court reporters write things phonetically and by the syllable, switching from Midwestern names like Jonesville, Detroit, and Lansing to names like Palos Verdes, Aliso Viejo, and Santa Monica kept my fingers working overtime. When “Rancho Cucamonga” came up, I wanted to say, “Aw, come on! Now you’re just making stuff up!” There’s nothing ending with “ville” here.

My job at the courthouse was to be a floating court reporter. We didn’t have those in Lansing, Mich., so I was a little unsure what to expect. Basically, unless assigned to a trial, I was working in a different courtroom with different staff every day. I would cover for assigned reporters on vacation, or I would work in a courtroom with no assigned reporter. Learning the ins and outs of each courtroom was a little daunting, and it made it difficult to make friends at first. I would cover criminal, civil, family law, and probate proceedings. Each area has its own distinct vocabulary, so coming up with brief forms for words like “conservatorship” and “income and expense declaration” became a necessity.

I started my job in December, so things were definitely slower around the holidays than the rest of the year. I think the hardest thing to wrap my head around was the fact that I was still getting a paycheck for the same amount every week whether I was in the courtroom all day or getting some office time. Not yet grasping that concept, I thought, when I didn’t have a backlog of transcripts to work on, how was I going to have any income? I’ve always had a transcript backlog for the past 28 years. No backlog equals no income equals no job stability equals no rent payment. I panicked over this the first couple of months before realizing the whole stability-of-a-paycheck thing.

The hours at the new job are also very different. They are 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. with a lunch break. The traffic wouldn’t allow me to get home to let my dogs out and then back over the lunch break, so I had to hire a dog walker to come every day at lunch to walk and feed them. It was dark when I left for work in the morning and dark when I came home. It seemed every waking hour was spent at work. When I came home, I’d walk and feed the dogs and fall into bed, exhausted and overwhelmed.

On a brighter note, the cool thing about 8 to 5 and no heavy transcript load is that, for the first time in my life, my weekends were mine. As the days grew longer, the evenings became mine as well. For the last 28 years, every time I’d tried to do a vacation or yard work or anything besides transcript work, in the back of my mind would be a little voice saying, “You should be in your office working on that transcript.” Suddenly, there were no transcripts I was expected to work on that couldn’t be done on my lunch break or off time in my office. Suddenly, my time was actually mine, and that space in my mind had been cleared. For the first time in a long time, I was able to live in the moment and more fully enjoy my life.

As things settled in over the next few months, I made some work friends and settled into a rhythm that became comfortable. I found favorite courtrooms, and the scheduler would try to keep me in my favorites when possible. Eventually, I got to transfer to a courthouse that was closer to home, and I could go home for lunch to take care of my puppsters. There were fewer courtrooms in the new building and, just like in the previous building, I found favorites and am lucky to have a scheduler who tries to keep me where I’m happiest. I’ve made new friends and am happy to go to a building filled with people I can talk to each day versus working from my home and living a life of only isolation and work.

My manager must have been a saint because, man, those first few months I can’t count the number of times he heard me say, “Well, in Michigan we do it this way.” I’m sure in his mind he was thinking, “Well, you’re not in Michigan anymore.”

A few examples of differences would be no one orders mini transcripts or word indexes here. I don’t know how they find anything without reading the entire transcript.

In Michigan, each day yields a new volume beginning with Page 1. In California, multiple days can be put into one volume, and page numbering is consecutive. This means, if you took 15 pages of an appeal one day, you need to wait for the reporter who took 2,000 pages before you to finish their portion to give you a starting page number. Oh, how I miss the days when I could do my 15 pages, get it off my desk, and not think about it again.

In Michigan, once the original transcript is prepared, they use the same transcript for the appeal. In California, an attorney may order daily copy and receive the originals; however, if they appeal, the reporter needs to prepare a different version of the same transcript with a different cover page and different index. The attorney must pay for the transcript again. If they ordered real-time and/or a daily rough, they could end up paying for different versions of the same transcript three or four times.

In Michigan, starting, ending, and break times are put on the record. In California court (at least in mine), the clerk is responsible for recording the times. The reporter simply puts “On the record,” “Off the record,” and “Proceeding concluded” in the record.

This COVID-19 period of isolation is kind of like stepping back in time for me, in that I was accustomed to being home a lot and working from home in Michigan. I’m trying to see it as a writing opportunity, but I look forward to returning to the bustle of a courthouse full of people to talk to. I still haven’t found a brief form for “Rancho Cucamonga,” but maybe this period of isolation will be my opportunity to do that.

Happy Reporting!

Kristie Dickinson, RPR, CRR, is an official court reporter in Anaheim, Calif. She is the author of the Harbor Secret Series, the Nine Days In Greece Series, and the award-winning screenplay The Other Christmas List, all available on Amazon. She blogs about her move to California at Daterella.wordpress.com.

[…] https://www.thejcr.com/2020/04/14/working-in-the-new-world-of-official-court-reporting/ […]