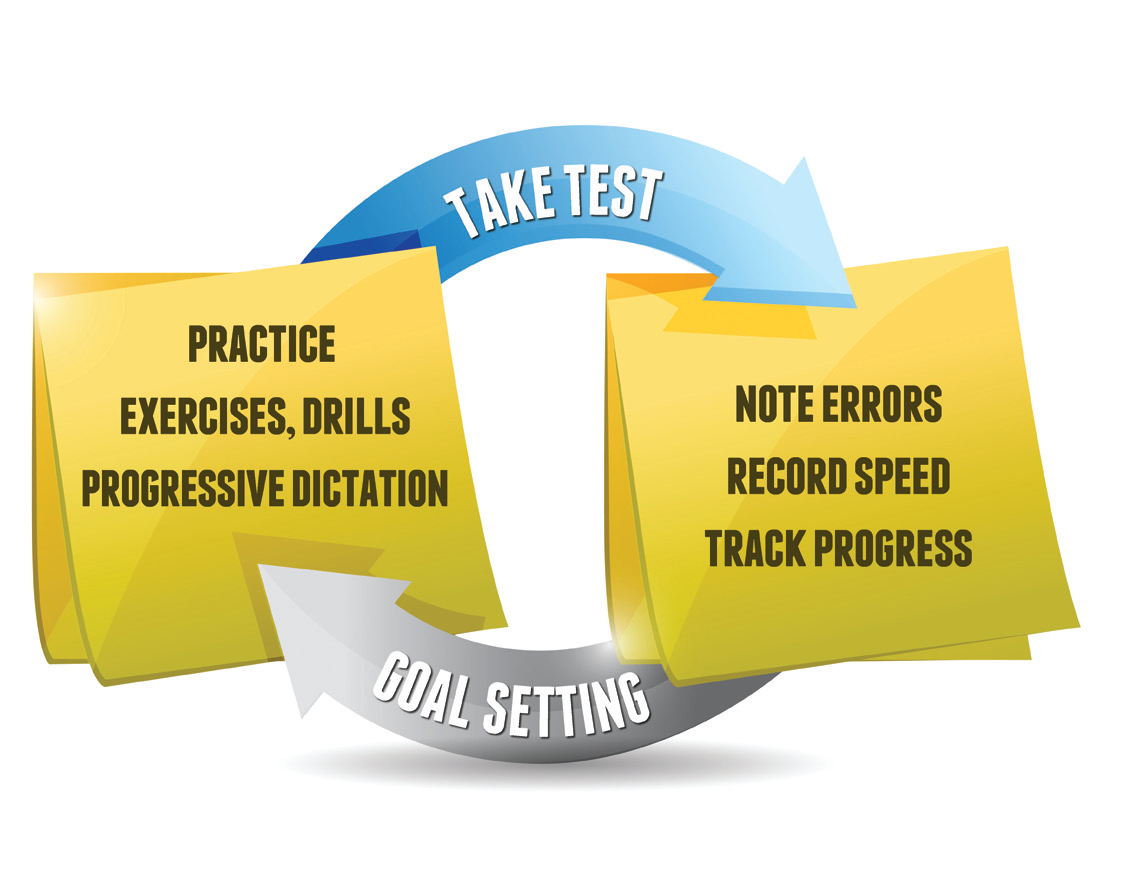

At some point, every court reporting student is asked to read back everything they write, practice the challenging words and briefs in an effort to be perfect, or track their tests to see progress over time rather than just focusing on passing a particular speed,” says Lynette R. Eggers, MBA, MA, CRI, CPE, CPC, NCRA’s assistant director of educational services. “Whether as a student or a working reporter, tapping into feedback loops can help you improve your writing, speed, or stamina.”

At some point, every court reporting student is asked to read back everything they write, practice the challenging words and briefs in an effort to be perfect, or track their tests to see progress over time rather than just focusing on passing a particular speed,” says Lynette R. Eggers, MBA, MA, CRI, CPE, CPC, NCRA’s assistant director of educational services. “Whether as a student or a working reporter, tapping into feedback loops can help you improve your writing, speed, or stamina.”

These long-standing techniques are examples of tapping into feedback loops. Feedback loops, a term used by scientists and mathematicians, explain phenomenon in different disciplines but with similar tendencies toward growth or stability. An example of a positive feedback loop is the use of traffic monitoring signs that are placed on some roads and show a car’s speed as it approaches. Although the information is redundant — the same information on the car’s speedometer — police reports show that people speeding near the signs do slow down. In this case, getting information about the car’s speed leads to a change in behavior. A negative feedback loop is a system that tends toward stability, not toward depletion, and an example might be a thermostat setting in a house. The heating system is set to turn off when it reaches a specific temperature, say 70°, and turn back on if it drops below that, maintaining a stable environment.

In the psychology of learning, a negative feedback loop denotes a self-correcting one (stability) while a positive feedback loop denotes a self-reinforcing process (growth). Reading back to find and recognize errors – and therefore correct them –is an example of a self-correcting system. Tracking tests reinforces progress made, a self-reinforcing method.

IT’S ALL ABOUT MONITORING

The growth in technology is changing how people use feedback loops. People are using everything from monitors in running shoes to mobile apps in phones to track teenagers driving speed and location. What the technology truly does, however, is make this sort of tracking easy and provides feedback that people can immediately act on.

Likewise, working reporters and students who are seeking to improve their writing can use realtime to receive immediate feedback. CAT software can track translation rates. Alternatively, there are many speedbuilding programs now on the market. Many of the programs can track errors and offer personal suggestions for exercises to practice, provide alternative briefs for tricky fingering, create specific drills, or give progressive dictation.

LOW-TECH APPROACHES

LOW-TECH APPROACHES

There’s no need to go high-tech, however. For years, financial advisers and dieticians working with people who were tackling new budgetary or weight goals offered the same piece of advice: “Write it down.” A pencil and a pad of paper or a chart kept on your computer applied with a little self-discipline can help court reporters and students note their errors and track their progress from one day to the next.

“To work on accuracy, we should go through what we’ve written and create a list of the words that didn’t translate, we dropped or creatively wrote. Once we have a list, we should see if there are any patterns, such as consistently writing the same prefix wrong, or certain boundary issues. In some cases, we may want to practice writing certain words or word groups. Pulling out that theory book, from under the bed, blowing off the dust, and reviewing a particular lesson is always a good place to start. In other situations, we may need to analyze whether a better solution would be to make additional entries in our dictionaries so that the errors translate correctly or to deal with some of the more challenging issues,” say Eggers. While working reporters will probably tackle these issues as they need to, Eggers recommends that students stick with the practice option and only consider changes to the dictionary after they’ve talked to their teachers about what kind of impact such changes would have on the dictionary as a whole.

It’s difficult to work only on speed without also taking into account a person’s accuracy, Eggers notes. Whether pushing for a higher speed to pass a certification exam or to build stamina for a fast talker, gaining speed takes practice. Some reporters suggest practicing dictation takes at 10 or 20 words higher than the target speed to gain speed. Others suggest that, especially for test-takers, practicing at the exact speed and for the exact length of the exam prepares reporters for the circumstances as closely as possible.

In either case, tracking improvements over the course of several practices can help keep reporters motivated by showing progress. Tracking progress, as with weight control or finances, also reinforces good behavior and shows when people slip up (which we all do), encouraging them to get back on track toward their goals, an example of a negative feedback loop. Research on how monitoring aids people in meeting goals in other areas has shown that such tracking is essential in meeting and maintaining goals. People who give up and stop tracking also tend to have more difficulty meeting those goals.