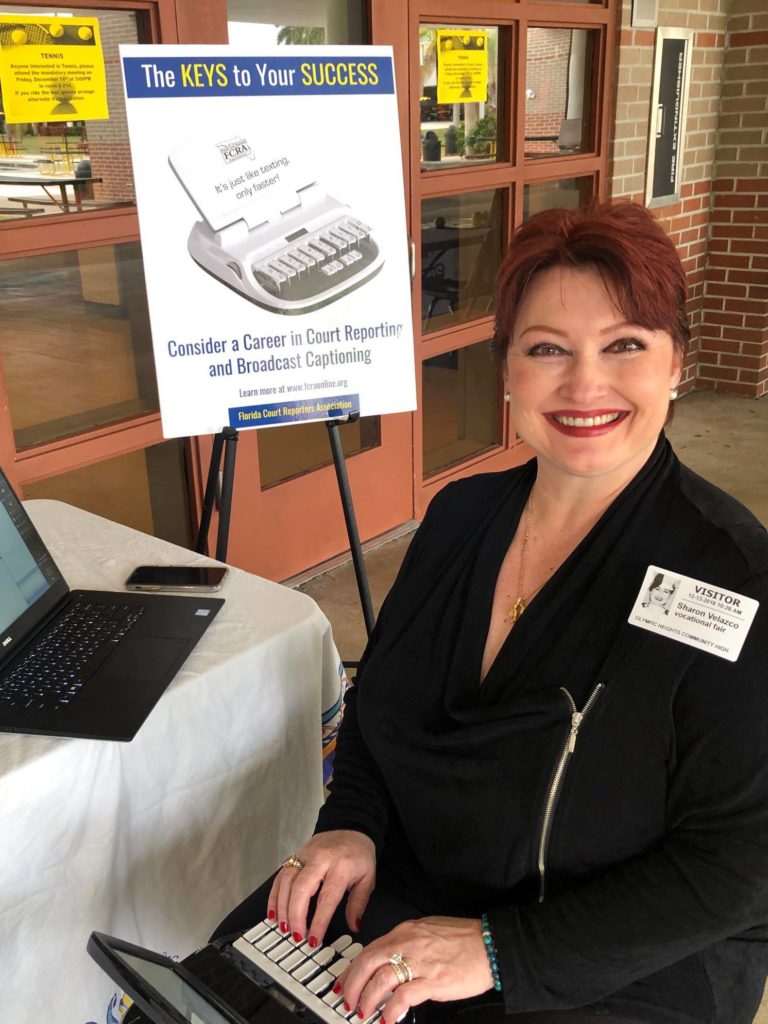

By Sharon Velazco, RPR

I was recently amused when I came across the article in which accomplished

female judges and attorneys were interviewed, and they were relating instances

in their career when, because of their gender, they were mistaken for the court

reporter. And, although I am sure it is not the intention of the author, the

tone of the article assumes that to be mistaken for the court reporter would be

somehow demeaning. So, to the average reader who has probably never met a court

reporter, I would like to explain what it is that court reporters do and how it

is actually an honor and privilege to be a member of this niche, necessary

profession which, ironically, given the theme of the article, was once mostly

held by men.

There’s a common tenet in the medical community, “If it’s not written down, it didn’t happen,” referring to the importance of a written record in the care and treatment of a patient. The same premise may be applied to the legal process. The written record is the foundation of our system of justice, and court reporters are the scribes and keepers of that written record. That same written record will be needed and relied on by the jurist in order to prepare and advance her case. In our American institution of jurisprudence, the legal process is dependent on the written record — the record prepared by the court reporter.

Contrary to popular belief, this is not a skill which is acquired in a few weeks or that can be performed by just anyone. This is not just a job. This is a chosen career. The uniquely qualified individual will spend an average of two to three years to complete the basic training necessary to become a court reporter. It takes about a year just to learn the stenographic theory of the writer, and then the remainder of the time is spent building speed, accuracy, and taking other classes to complement the knowledge base needed to produce a transcript. In addition to the obvious requirement for advanced English and grammar, there is the prerequisite for legal and medical terminology. It is often necessary to study a wide range of material in order to be prepared to take down the specific, vital testimony of a doctor, engineer, or other expert witness whose opinion may be crucial to a case. There is no script from which to prepare until the court reporter writes it — in realtime.

Additionally, the qualities of innate human intuition and skill combined with modern technology provides for real-time capturing of the spoken word to text in a readable, usable format, regardless of accent or subject matter. So whether that court reporter is working in a legal setting and giving realtime, immediate access to the transcript, or perhaps working behind-the-scenes doing the closed captions for a television broadcast, please know that it takes a special kind of talent, dedication, and determination to achieve the level of skill required to provide that invaluable service. And, while the closed captions are, without a doubt, appreciated by the viewer, that viewer is probably unaware that it’s all being done by a court reporter.

So, in summary, this occupation is a challenging, constant education-in-process. This occupation is flexible, exciting, and never boring. This occupation offers opportunities to travel the world. This occupation also happens to be extremely rewarding financially. So, without taking away from the successful careers and accomplishments of our respected members and leaders of the legal community whose experiences were the basis of the original article, let me turn the article’s slant the other way. I would like to ask that author, now that they know a little about what we do, who wouldn’t want to be the court reporter?

Sharon Velazco, RPR, is a freelance court reporter based in Miami, Fla. She can be reached atscribe3159@aol.com.